|

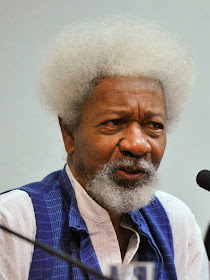

| Wole Soyinka, 2015 |

Friday, December 14, 2018

Adrienne Rich, American Skeptic

ADRIENNE RICH, AMERICAN SKEPTIC

Adrienne

Rich has been recognized as one of the most

influential poets in the U.S. the past several decades. She

She

came of age as a political activist during the turbulent counter-culture of the

sixties. Her activism coincided with the rise in the U.S. of second wave

feminism and the beginning of the modern gay liberation movement. The latter is

usually dated to the Stonewall riots on June 28, 1969.

Poet

and essayist, Rich is a very influential, articulate, and sophisticated

literary voice advancing two major contemporary liberation movements, feminism

and LGBT rights, or lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights. Her beacon,

multi-awarded track record is documented, for example, in Poetry magazine:

Feminism

and LGBT rights are each loci of complexly related issues with worldwide reach.

They are international liberation movements centered in the U.S. and Western

Europe mainly. Although Rich is known and celebrated in the U.S. primarily, as

a contemporary leader of feminism and LGBT rights, her influence is global.

As

a prominent feminist, Rich’s global influence is a given. After all, the

varieties of contemporary feminism are a direct concern of a little less than

half the world population.

As

an advocate for LGBT rights, her influence is also substantial because the

LGBT population worldwide is considerable. The cat is out of the closet, so to

speak. Today, entire societies cannot but be majorly occupied with issues related to the

treatment—legal, political, social, and economic—of this salient minority

group.

One

of the largest minority groups in any country is that of the LGBT population. It

is difficult to estimate the actual count because as a rule acknowledging your

LGBT identity, whether in surveys or elsewhere, is taboo. Besides, homosexual

activity is illegal in 73 countries.

Still,

we can go by the results of scientific and professional surveys. In 2017 a

Gallup survey found that 4.5% of the total U.S. population or over 11 million Americans

self-identified as LGBT. If the proportion of the total world population that self-identifies

as LGBT is in this vicinity—a reasonable suggestion—then we can conclude that out

of a total world population of 7.5 billion in 2017, up to 337.5 million people would

probably self-identify as LGBT. The proportion may be small, but the number is considerable.

See:

—“In U.S., Estimate of LGBT Population Rises to 4.5%,” Gallup (May 22, 2018) by Frank Newport

Towards the end of her life, Rich described herself as an “American Skeptic.” The moniker is appropriate for someone, keenly intelligent, who sought to deconstruct the social structures that constrain the advancement of her two lifetime occupations, feminism and LGBT rights. Deconstruction is the province of the intellectual skeptic.

“I

began as an American optimist, albeit a critical one, formed by our racial

legacy and by the Vietnam War…I became an American Skeptic, not as to the long

search for justice and dignity, which is part of all human history, but in the

light of my nation's leading role in demoralizing and destabilizing that

search, here at home and around the world. Perhaps just such a passionate

skepticism, neither cynical nor nihilistic, is the ground for continuing.”

—Adrienne

Rich, Los Angeles Times (March 11,

2001)

The

above quote shows that Rich was critical of the reactionary exercise of global U.S.

power and influence.

“Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers” appeared in Adrienne Rich’s first book of poetry, A Change of World (1951), published when she was only 22 years old. The collection of 40 poems won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award.

“Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers” appeared in Adrienne Rich’s first book of poetry, A Change of World (1951), published when she was only 22 years old. The collection of 40 poems won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award.

AUNT

JENNIFER’S TIGERS

Aunt

Jennifer’s tigers prance across a screen,

Bright

topaz denizens of a world of green.

They

do not fear the men beneath the tree;

They

pace in sleek chivalric certainty.

Aunt

Jennifer’s finger fluttering through her wool

Find

even the ivory needle hard to pull.

The

massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band

Sits

heavily upon Aunt Jennifer's hand.

When

Aunt is dead, her terrified hands will lie

Still

ringed with ordeals she was mastered by.

The

tigers in the panel that she made

Will

go on prancing, proud and unafraid.

The

poem deals with the motif of feminism, which Rich would maintain in her poetry throughout

her life.

The

poem is understated, straightforward, and not especially difficult. Once the

reader realizes that the “tigers” are embroidered designs in a woolen field,

the overt meaning of the poem is readily apparent. The “massive weight” of Aunt

Jennifer’s “wedding band” is a giveaway indicating that Aunt Jennifer’s marriage,

and by extension the institution of marriage, is a type of social oppression. The

poem describes her hands at death as still bound, “ringed” with “ordeals” and frozen

in terror. They are the same hands that created the tigers that prance freely, “proud

and unafraid” of the “men beneath the tree.” Manifestly, the tigers symbolize freedom

from the oppression of patriarchy.

Published in 1957, “A Ball Is for Throwing” is occupied with feminist and gay liberation motifs. Key to its interpretation is getting a fix on what the ball stands for.

A BALL IS FOR THROWING

Published in 1957, “A Ball Is for Throwing” is occupied with feminist and gay liberation motifs. Key to its interpretation is getting a fix on what the ball stands for.

A BALL IS FOR THROWING

See it, the

beautiful ball

Poised in the

toyshop window,

Rounder than

sun or moon.

Is it red? is

it blue? is it violet?

It is

everything we desire,

And it does

not exist at all.

Non-existent

and beautiful? Quite.

In the

rounding leap of our hands,

In the

longing hush of air,

We know what

that ball could be,

How its blues

and reds could spin

To a headier

violet.

Beautiful in

the mind,

Like a word

we are waiting to hear,

That ball is

construed, but lives

Only in flash

of flight,

From the

instant of release

To the catch

in another’s hand.

And the toy

withheld is a token

Of all who

refrain from play—

The

shopkeepers, the collectors

Like Queen

Victoria,

In whose

adorable doll’s house

Nothing was

ever broken.

The

poem cites two toys: the ball and the doll’s house. The latter, a girl’s toy,

is for those who, like shopkeepers and Queen Victoria, “refrain from play,” and the ball is “the toy withheld” from them. In the last

stanza it is apparent that the ball is a boy’s toy, so that it is a symbol of

masculine identity, just as the doll’s house is a symbol of feminine identity.

Significantly,

the ball is spoken of in positive, liberating terms. It represents many

possibilities—it can spin its blues and reds into violet, it is “beautiful in the mind” when it is

thrown, “it is everything we desire.”

Symbolically, the poem protests the assignment of sex-typed roles to males and

females. By extension, it also critiques the male-female dichotomy qua social institution that is the basis for

sex-typing.

“What Kind of Times Are These” is a protest poem, understated and allusive. At the time of publication in 1995 Rich was in her mid-sixties.

WHAT KIND OF TIMES ARE THESE

“What Kind of Times Are These” is a protest poem, understated and allusive. At the time of publication in 1995 Rich was in her mid-sixties.

WHAT KIND OF TIMES ARE THESE

There’s

a place between two stands of trees where the grass grows uphill

and

the old revolutionary road breaks off into shadows

near

a meeting-house abandoned by the persecuted

who

disappeared into those shadows.

I’ve

walked there picking mushrooms at the edge of dread, but don’t be fooled

this

isn’t a Russian poem, this is not somewhere else but here,

our

country moving closer to its own truth and dread,

its

own ways of making people disappear.

I

won’t tell you where the place is, the dark mesh of the woods

meeting

the unmarked strip of light—

ghost-ridden

crossroads, leafmold paradise:

I

know already who wants to buy it, sell it, make it disappear.

And

I won’t tell you where it is, so why do I tell you

anything?

Because you still listen, because in times like these

to

have you listen at all, it’s necessary

to

talk about trees.

The

poem is about a place, and when we examine this place closely, it is marked by disquiet

and in some way cursed and threatened. It is “near a meeting-house abandoned by

the persecuted who disappeared,” which suggests a political context. “Our

country,” the speaker says, is moving in the direction of “truth and dread,” and

because the speaker alludes to Russia, a country where people are made to disappear,

the meaning of this statement is political. As people have been made to

disappear, the speaker continues, the place risks the same fate. The poem is

political but in an unassuming sort of way.

Why

speak about this place, “about trees”? Because “to talk about trees” primes the

audience to listen, and since the import of the poem is political, that about

which the poem acts as a preparation is therefore of political significance—“because

in times like these / to have you listen at all, it’s necessary / to talk about

trees.”

Rich

alludes to Bertolt Brecht’s “An die

Nachgeborenen” or “To Those Who Follow in Our Wake,” published in 1939. Excerpt

from the first stanza:

Wirklich, ich lebe in finsteren

Zeiten!...

Was sind das für Zeiten, wo

Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein

Verbrechen ist

Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele

Untaten einschließt!

This

poem was originally published in Svendborger

Gedichte (1939).

English translation:

Truly,

I live in dark times!...

What

times are these, in which

A

conversation about trees is almost a crime

For

in doing so we maintain our silence about so much wrongdoing!

Translation was originally published in Gesammelte Werke, Volume 4, (1967), S.H. transl.

Translation was originally published in Gesammelte Werke, Volume 4, (1967), S.H. transl.

Brecht

laments that in Nazi Germany, citizens maintain conversations about “trees” because they are constrained to keep silent about Nazi depravity. Their

silence is “almost a crime.”

Once

we recognize Rich’s allusion to Brecht, it is apparent that her poem is

political. The poem protests the unavoidably indirect manner by which difficult

issues must be presented to a resistant audience.

|

| Adrienne Rich, undated photo |

Langston Hughes, Foremost Poet of the Harlem Renaissance

LANGSTON HUGHES, FOREMOST POET OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE

The

poetry of protest and resistance arouses our critical attention because

it represents a major type of world literature. This type of literature is often associated

with liberation movements.

What is a “liberation movement”?

“A

liberation movement is a type of social movement that seeks territorial

independence or enhanced political or cultural autonomy (or rights of various

types) within an existing nation-state for a particular national, ethnic, or

racial group. The term has also been extended to or adopted by other types of

groups (e.g., women and gays and lesbians) that seek to free themselves from

various forms of domination and discrimination. National liberation movements

have been an especially important force in the modern world…The division of the

globe into nation-states, many of the wars among these states, and the hundreds

of historical and contemporary conflicts among states and ethnic groups—in

short, fundamental aspects of the modern world—cannot be understood without

also understanding liberation movements.”

Although pro-democracy movements or armed left-wing insurgencies usually come to mind when we think of liberation

movements, they also arise from the right wing, e.g. Islamist groups like Al Qaeda,

ISIS, or the Taliban. Palestinian nationalism is a type of liberation movement.

Notably, authoritarian regimes and those incorporating varying degrees of authoritarianism characterize the majority of political systems today. Notwithstanding, political authoritarianism, rather than extinguishing liberation movements, incites them. They cannot be just switched off because they arise when oppressed groups resist social injustice, real or imagined, and seek structural redress.

The U.S. civil rights movement has been one of the most signal liberation movements in modern world history. Undertaken and led largely by African Americans—when we say “African Americans,” we mean the U.S. black population mainly—and directed against legally sanctioned racial segregation and discrimination in U.S. society—the U.S. civil rights movement was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance, and possibly for this reason the movement was exceptionally successful in achieving its goals, at least in the political and legal aspects.

Notably, authoritarian regimes and those incorporating varying degrees of authoritarianism characterize the majority of political systems today. Notwithstanding, political authoritarianism, rather than extinguishing liberation movements, incites them. They cannot be just switched off because they arise when oppressed groups resist social injustice, real or imagined, and seek structural redress.

The U.S. civil rights movement has been one of the most signal liberation movements in modern world history. Undertaken and led largely by African Americans—when we say “African Americans,” we mean the U.S. black population mainly—and directed against legally sanctioned racial segregation and discrimination in U.S. society—the U.S. civil rights movement was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance, and possibly for this reason the movement was exceptionally successful in achieving its goals, at least in the political and legal aspects.

At least four

major areas of the U.S. political and legal system were reformed: U.S. Supreme Court rulings striking down Jim Crow legislation; the passage of federal civil rights laws; 1964

ratification of the 24th amendment; and the formation of federal

agencies tasked with civil rights agendas.

Despite the fact that racism still characterizes U.S. society today—it is an open scientific question

whether social discrimination based on racial or ethnic group differences can

be wholly eliminated—African Americans surely have come a long way from being regarded

as chattel to electing one of their own to the presidency of a superpower.

Ideologically, the U.S. civil rights movement has directly influenced liberation movements worldwide, notably, nonviolent pro-democracy movements in the Philippines, Eastern Europe, China, Myanmar, “Arab Spring” countries, Ukraine, and Hong Kong (special administrative region of China), and feminist, gay rights, or indigenous people movements, which cut across individual nations. Not all pro-democracy movements have been successful.

At least 42 million blacks or about 14 percent of the U.S. population today are direct beneficiaries of the U.S. civil rights movement. This positive influence extends not only to the U.S. black population but also to other peoples of color in U.S. society.

Although

it is difficult to quantify the global impact of the U.S. civil rights movement in

terms of the total population affected, we can confidently say that its influence encompasses

a broad swath of past and ongoing liberation movements, so that the total number readily adds

up to the hundreds of millions.

The most important leader of the U.S. civil rights movement was Martin Luther King Jr. In this role he had a major influence on liberation movements arising since the sixties until the present time.

Between

King and Langston Hughes, the former was my first choice for inclusion in my

second list of ten greatest poets.

King?—a poet?

Look

at major portions of his famous 1963 speech, “I Have a Dream,” and tell me it

isn’t poetry:

Let

us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And

so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a

dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I

have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true

meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men

are created equal.”

I

have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former

slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at

the table of brotherhood.

I

have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering

with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be

transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I

have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where

they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their

character.

I

have a dream today!

Eventually,

I eliminated King from my list of candidates for ten greatest poets, numbers 11

to 20, because he was a civil rights activist first, a poet second. In

contrast, Langston Hughes was a poet first, a political activist second.

Similarly,

I eliminated Maya Angelou from my list of candidates because I see her as a

political activist first, a poet second. Although I readily acknowledge Angelou’s

popularity and influence, especially in the U.S., I do not find her poetry qua

poetry, especially distinguished.

One

reviewer, for example, has described her poetry as “Hallmark.” See “The Awfully

Good Activism and Terribly Bad Poetry of Maya Angelou”:

—“The Awfully Good Activism and Terribly Bad Poetry of Maya Angelou,” Daily Review (August 15, 2016) by Helen Razer

—“The Awfully Good Activism and Terribly Bad Poetry of Maya Angelou,” Daily Review (August 15, 2016) by Helen Razer

Poetry magazine is far

kinder, saying she would perform her poetry before spellbound crowds. The article celebrates her connection to “African-American oral traditions

like slave and work songs, especially in her use of personal narrative and

emphasis on individual responses to hardship, oppression, and loss,” adding that

besides individual experience, she would “often respond to matters like race

and sex on a larger social and psychological scale.”

Langston Hughes is in my second list of ten greatest poets because he was the foremost poet of the Harlem Renaissance, a direct precursor of the U.S. civil rights movement, which has been and continues to be enormously influential worldwide, especially among liberation movements that espouse nonviolence.

Why is Langston Hughes the foremost poet of the Harlem Renaissance? We suggest that he wrote some of the most poignant, memorable, and finely crafted poems of the movement, and as a result stood out from the rest. At one point he was described as the “poet laureate of black America.”

I have selected several of Hughes’ most famous poems for analysis and commentary. They are vibrant examples of his work.

HARLEM

What

happens to a dream deferred?

Does

it dry up

like

a raisin in the sun?

Or

fester like a sore—

And

then run?

Does

it stink like rotten meat?

Or

crust and sugar over—

like

a syrupy sweet?

Maybe

it just sags

like

a heavy load.

Or does it

explode?

This poem was originally published in Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951).

Hughes

wrote multiple poems about dreams—“Dreams,” “I Dream a World,” “As I Grew Older,”

or “Let America Be America,” for example. Hughes’

“dream poems” allude to the “American Dream,” defined as follows:

“The

ideals of freedom, equality, and opportunity traditionally held to be available

to every American” and “A life of personal happiness and material comfort as

traditionally sought by individuals in the U.S.”

The

term “American Dream” was coined in 1931 by James Truslow Adams (1878-1949) in “Epic

of America”:

“…[as]

that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for

everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. It is

a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and

too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a

dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which

each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which

they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are,

regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”

“Harlem”

invokes a series of metaphors that unmistakably convey in negative terms the

denial to African Americans of the American Dream. Their disenfranchisement is a

“festering sore,” “rotten meat,” or “heavy load.”

Also

popularly known as “Dream Deferred,” “Harlem” has been described as prophetic. “Dream

deferred,” Hughes says in the poem, will at some point “explode,” which is

exactly what happened several years after the poem was published, when during

the U.S. civil rights movement African Americans successfully fought against Jim

Crow.

Critics connect the content of Martin Luther King’s writings directly to Langston

Hughes, especially “I Have a Dream,” King’s August 28, 1963 speech at the

Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., and his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” published

on April 16 the same year.

See, for example:

—“How Langston Hughes’s Dreams Inspired MLK’s,” Smithsonian.com (February 1, 2017) by Kat Eschner

—“Langston Hughes’ hidden influence on MLK,” The Conversation (March 30, 2018) by Jason Miller

See, for example:

—“How Langston Hughes’s Dreams Inspired MLK’s,” Smithsonian.com (February 1, 2017) by Kat Eschner

—“Langston Hughes’ hidden influence on MLK,” The Conversation (March 30, 2018) by Jason Miller

King

did not acknowledge this literary debt because he was careful to distance

himself from Hughes who had in the past flirted with communism. Well aware that

opponents of the U.S. civil rights movement would seek to undermine it—and they

did so with some success—with blown-up charges of communist sympathy and affiliation,

King made a decision that was based on intelligent politics.

Was

Hughes a Communist? Depends on how you want to answer this question.

Two possible answers: “No” and “Nearly so.”

“No”—Hughes was never a member of the Communist party, he did not explicitly profess Communist ideology, and he never identified himself as a Communist.

“Nearly so”—Hughes was sympathetic toward Communism in the thirties, a period of major ideological flux and political upheaval in the U.S. and Europe. His political leanings should not surprise us because Communist ideology champions the struggle of the economically oppressed, which includes the racially oppressed blacks. Hughes’ poems were frequently published in the newspaper of the Communist Party of the U.S., and in 1938 he signed a statement supporting Stalin's purges. He supported causes pushed by Communist organizations, such as the drive to free the Scottsboro Boys and the side of the Spanish Republic, and he showed sympathy for Communist-led organizations like the John Reed Clubs and the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. In the fifties, however, he began to distance himself from his left-leaning past. His Selected Poems published in 1959, for example, omitted his radical poetry.

“I, Too,” like “Harlem,” protests the social oppression of blacks in the U.S. However, it does not make the same point so directly.

I, TOO

“No”—Hughes was never a member of the Communist party, he did not explicitly profess Communist ideology, and he never identified himself as a Communist.

“Nearly so”—Hughes was sympathetic toward Communism in the thirties, a period of major ideological flux and political upheaval in the U.S. and Europe. His political leanings should not surprise us because Communist ideology champions the struggle of the economically oppressed, which includes the racially oppressed blacks. Hughes’ poems were frequently published in the newspaper of the Communist Party of the U.S., and in 1938 he signed a statement supporting Stalin's purges. He supported causes pushed by Communist organizations, such as the drive to free the Scottsboro Boys and the side of the Spanish Republic, and he showed sympathy for Communist-led organizations like the John Reed Clubs and the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. In the fifties, however, he began to distance himself from his left-leaning past. His Selected Poems published in 1959, for example, omitted his radical poetry.

“I, Too,” like “Harlem,” protests the social oppression of blacks in the U.S. However, it does not make the same point so directly.

I, TOO

I,

too, sing America.

I

am the darker brother.

They

send me to eat in the kitchen

When

company comes,

But

I laugh,

And

eat well,

And

grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll

be at the table

When

company comes.

Nobody’ll

dare

Say

to me,

“Eat

in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll

see how beautiful I am

And

be ashamed—

I,

too, am America.

This poem was originally published in The Weary Blues (1926).

This poem was originally published in The Weary Blues (1926).

The vignette cuts to the chase—consigned to eat in the kitchen, the

speaker laughs, eats well, and grows strong. No bitterness here, we sense, but

rather self-assurance. He knows the indignity is temporary.

Seeing

the future, he foretells that it is his oppressors who will be shamed, not him.

He, the darker brother—they will see how beautiful he is.

Chiding,

the protest is powerfully understated.

The

opening and closing lines, symmetrical, allude to Walt Whitman’s “I Hear

America Singing,” sealing the poem, unifying it.

This last poem, “Po’ Boy Blues” is written in a variety of the slave dialect that over generations has changed and varied.

PO’ BOY BLUES

This last poem, “Po’ Boy Blues” is written in a variety of the slave dialect that over generations has changed and varied.

PO’ BOY BLUES

When

I was home de

Sunshine

seemed like gold.

When

I was home de

Sunshine

seemed like gold.

Since

I come up North de

Whole

damn world’s turned cold.

I

was a good boy,

Never

done no wrong.

Yes,

I was a good boy,

Never

done no wrong,

But

this world is weary

An’

de road is hard an’ long.

I

fell in love with

A

gal I thought was kind.

Fell

in love with

A

gal I thought was kind.

She

made me lose ma money

An’

almost lose ma mind.

Weary,

weary,

Weary

early in de morn.

Weary,

weary,

Early,

early in de morn.

I’s

so weary

I

wish I’d never been born.

This poem was originally published in The Weary Blues (1926).

This poem was originally published in The Weary Blues (1926).

Some in the Harlem Renaissance opposed this type of literature because, they said, it depicts African Americans in a demeaning light—poor, uneducated, repellent, in some instances involved in immorality or crime. Critical of Hughes’ poetry collection, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), Estace Gay, for example, argued “our aim ought to be [to] present to the general public, already misinformed both by well meaning and malicious writers, our higher aims and aspirations, and our better selves.”

Not

all critics were so urbane. The Chicago Whip,

for instance, according to Hughes, characterized him as “the poet low-rate of

Harlem.”

See:

—“Langston Hughes: The People’s Poet,” National Museum of African American History & Culture (February 1, 2018) by Angelica Aboulhosn

—“Langston Hughes: The People’s Poet,” National Museum of African American History & Culture (February 1, 2018) by Angelica Aboulhosn

Hughes

responded graciously to his detractors.

“I

sympathized deeply with those critics and those intellectuals, and I saw

clearly the need for some of the kinds of books they wanted. But I did not see

how they could expect every Negro author to write such books. Certainly, I

personally knew very few people anywhere who were wholly beautiful and wholly

good. Besides I felt that the masses of our people had as much in their lives

to put into books as did those more fortunate ones who had been born with some

means and the ability to work up to a master's degree at a Northern college.

Anyway, I didn't know the upper class Negroes well enough to write much about them.

I knew only the people I had grown up with, and they weren't people whose shoes

were always shined, who had been to Harvard, or who had heard of Bach. But they

seemed to me good people, too.”

Today,

Hughes’ poems flourish because, precisely, they were written in dialect, or at

least, a dialect form adapted to Standard English. His social realism meaningfully engages contemporary readers. History has proven his approach correct.

“Po’

Boy Blues” is compelling not only for the realism of the dialect but also

because it portrays the hard luck circumstances of the speaker, which

authentically recapitulate the condition at the time of the migrant black

underclass.

The

poem draws the reader into the touching perspective of the black migrant from

the South, enters into his predicament steeped in pathos, and concludes with his lament, deeply evocative.

|

| Langston Hughes, 1942 |